Executive Summary

NGOs working on Syria and/or operating within the country have been confronted with rising obstacles since 2014 in their dealings with banks and financial institutions. Any mention of Syria is a red flag for banks and financial institutions. The report follows the process of payment mechanisms and financial operations faced by NGOs and INGOs, from opening the bank account, passing through transfer operations, to the consequences of related problems.

The research project provides a global analysis of the financial operations and challenges faced by NGOs (Syrian and non-Syrian), INGOs, and state and EU agencies starting from European countries to those neighboring Syria (Turkey, Lebanon, and Kurdistan Iraq) as well as Syria itself. Alongside these challenges in the financial circuit, the report analyses key problems encountered by humanitarian organizations posed by the various sanctions regimes in place and particularly those imposed by the US.

The study notes that NGOs and INGOs working on and/or in Syria have faced ever-increasing difficulties. Some have had to cancel projects because they could not keep up with the paperwork required by donors. Unfortunately, despite various global initiatives and conferences that have taken place in recent years between actors (NGOs and INGOs, states officials, and banking employees) to improve and facilitate the financial operations and transfers of NGOs working on or in Syria, there has been no significant progress made to date, frequently quite the opposite. While larger NGOs and INGOs can sustain some of the difficulties encountered in the obstacles and challenges posed by delays and blocking of financial operations (often because of the larger flows of money involved and larger compliance teams), more modest and smaller entities have suffered more.

This situation has not lessened the transfer of risks to the Syrian NGOs operating in the field in Syria or in neighboring countries, quite the contrary. As such, smaller humanitarian organizations are disproportionally affected by bank de-risking processes. Better provision of guidance and support by sanctions-enforcing bodies is welcome but is not enough to bypass the structural problems faced by humanitarian NGOs and INGOs operating in Syria or in neighboring countries, or in conflict zones more generally. The challenges faced by humanitarian NGOs and INGOs cannot be overcome on a case-by-case basis, but are structural in nature. They are rooted in the financial system and the current international sanctions framework.

Financial restrictions and de-risking

Humanitarian organizations, NGOs, and other Non-Profit Organizations (NPOs) have increasingly suffered in the past two decades from financial obstacles, resulting in negative consequences for their activities. Some of these processes have been called “de-risking”, referring to the practice of financial institutions putting an end to relationships with, and closing the accounts of, clients considered to be “high risk”, notably because of perceived risks of money laundering, terrorist financing, or being a designated entity or individual on an international sanctions list, while offering limited profitability returns.

In this context, individuals and organizations operating in high-risk countries may find themselves affected by de-risking, even if their financial transactions are legitimate. Rather than retaining and continuing to manage “risky” clients, financial institutions very often decide to end the relationship altogether, reducing their own risk exposure while leaving clients “unbanked”. The same also occurs with entire high-risk jurisdictions, whereby financial institutions frequently opt to withdraw their operations in, or in relation to, the country or cease them altogether; sometimes leaving them unbanked as well.

Many humanitarian NGOs operating in conflict zones such as Syria, Somalia, the Palestinian Occupied Territories, and Yemen have found themselves in this higher-risk category and were consequently disproportionately affected by de-risking processes. These processes have had particular repercussions on correspondent banking services, which have an important role in the mechanisms and flows of funding for NGOs, especially across borders. Many humanitarian NGOs rely heavily on correspondent banking services to transfer aid-related funds for program implementation and payment of staff abroad. Given the differences in regulatory norms existing between states, correspondent banks need to be certain that they are not facilitating the transfer of illicit funds from, or to, senders and recipients whose identities are unknown. They may, therefore, decide to put an end to relations with banks acting in a higher-risk environment to protect themselves against this likelihood, thus fracturing the chain. As corresponding banking channels are more vulnerable to fines and costs, they have instituted even more rigorous measures.

Any severing of mechanisms and flows of funding risk altering the ability of humanitarian organizations and NGOs to provide essential services and pay suppliers and staff salaries, with clear negative consequences. Financial restrictions on humanitarian organizations and NGOs have also had other negative effects, such as delays in wire transfers, requests for unusual additional documentation, increased fees, and account closures.

Dynamics of de-risking have notably led to the closure of orphanages in Lebanon and Sudan; the end of relief for persecuted minorities in Burma and the termination of school programs for students in Afghanistan as a result of direct severing of funds or in indirect ways, according to the Charity & Security Network report.

Syria has not been an exception regarding processes of “de-risking” and financial restrictions. Banks, exporters, transport companies, and insurance companies have, for example, nearly completely refused to

conduct business in Syria. Moreover, the lack of clarity of the various regimes of sanctions imposed on Syria has led risk-averse banks, insurance companies, shipping companies, and sellers of humanitarian goods, to choose to not engage with anyone or anything related to Syria (known more widely as the “chilling effect”).

Recommendations

For the international community and the European Union:

Involve CSOs:

Continue involving civil society initiatives from Syria and the Syrian diaspora and local European NGOs working in the region in the discussions on compliance, de-risking, and financial regulations alongside INGOs and banks as they deal with the burden of these regulations.

Clearer information:

Make information on what types of humanitarian assistance are permitted more accessible and facilitate exemption processes to sanctions and provision of licenses for Humanitarian and Relief INGOs and ONGs operating on and within Syria.

Legal advice:

Provide free or inexpensive legal advice and risk management guidance from governments, regional organizations, and the UN.

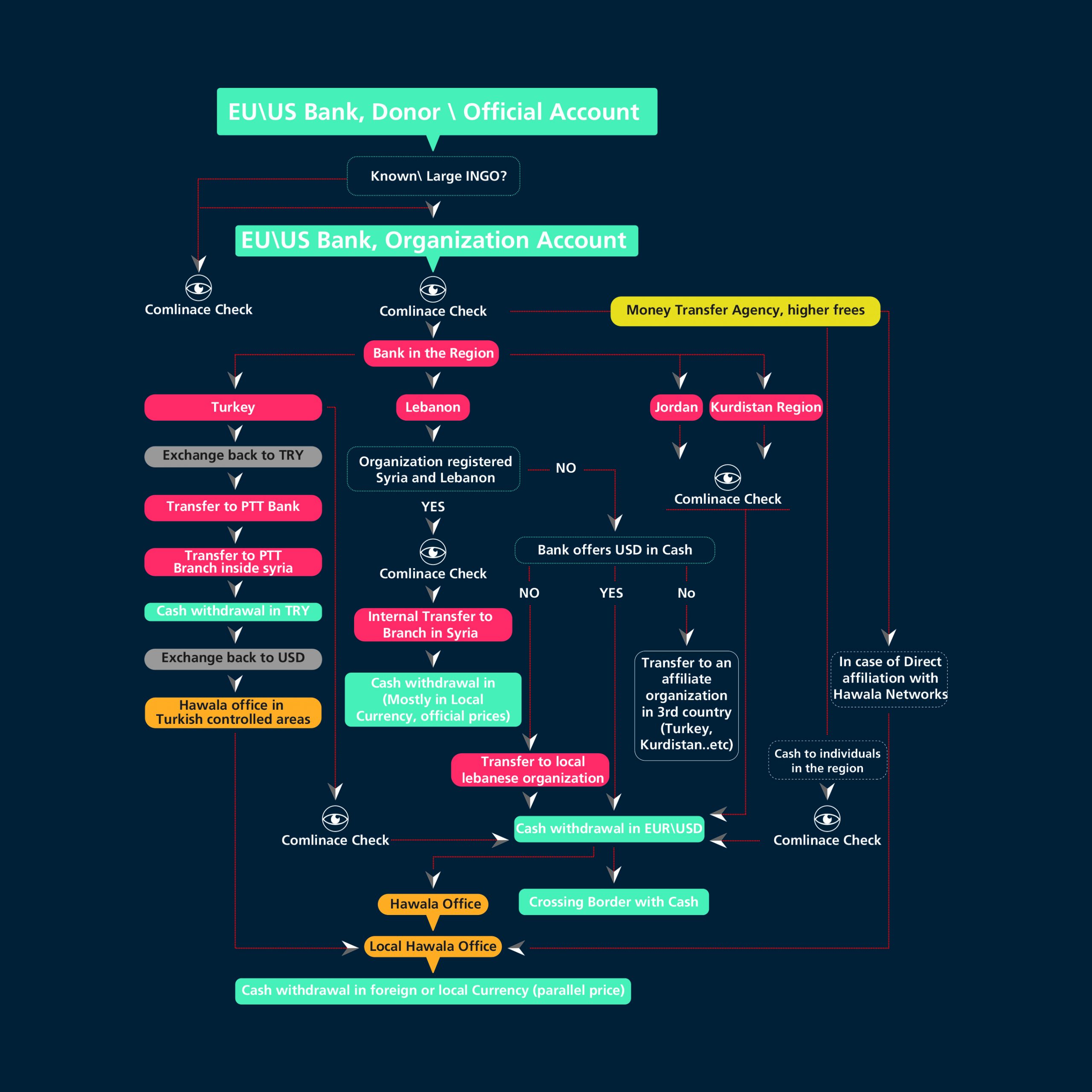

Help the Hawala system become more transparent:

Frequently, the hawala system is the only available instrument for fund transfer into areas with critical humanitarian and relief needs. States should help develop this system, supporting it to become more transparent and regulated.

Establish an independent financial institution:

Establish a financial institution with the singular duty to manage transactions for Humanitarian NGOs and INGOs operating or covering conflict zones without fearing the consequences of the sanctions regime. This bank could be created and funded by various international actors and donors.

Improve coordination:

Coordinate with European and US fiscal authorities for the dissemination of funds and regulation of tracking.

Mitigate the risk of harming the economy

Take measures within the sanctions framework to alleviate the risk of harming productive economic sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing as well as the Syrian population directly. This will also lessen the burden on NGOs and banks.

For banks:

Protect existing channels

Urgent protection is needed on the remaining banking channels in Syria to ensure the continuation of humanitarian assistance.

Standardize the system, provide clear guidance

Reach an agreement with the banks in coordination with INGOs and NGOs in order to provide them a unified and standard due diligence and compliance system on the types of information that are required to facilitate transfer of funds and other financial operations and procedures. Clear guidance is required on payment mechanisms, including correspondent banking channels, the extent of due diligence required, how to deal with the common problems (such as having Syria in the name, etc.)

Invest in fintech and AI

Invest research & development into fintech solutions and AI regarding improved software and tech-based innovations to improve and simplify compliance processes.

Research transparency development

Research how to allow for greater transparency in informal payment mechanisms, such as hawala systems and remittance networks.

For neighboring states

Ease the registration of new NGOs and branches to diaspora and European NGOs.

Introduce regulations that help NGOs comply with the local laws without fear of being prosecuted, such as registering their activities in the host countries but also in Syria, and registering NGO employees and contractors.